You are here

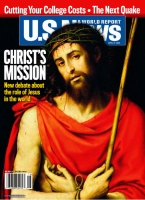

The Kingdom of Christ

A week or two back, there was a US News & World Report cover story of that same name with the sub-title "A bold new take on the historical Jesus raises questions about a centuries-long quest." It's mostly a discussion of the theories of James Tabor (professor of religious studies, UNC-Charlotte) which he describes in his book, The Jesus Dynasty: The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity. The article also describes the general direction of scholarship regarding Jesus and the origins of Christianity. Tabor's is another of those analyses of the story of Jesus, trying to distinguish what is perceived to be historical versus what is perceived to be fictional.

A week or two back, there was a US News & World Report cover story of that same name with the sub-title "A bold new take on the historical Jesus raises questions about a centuries-long quest." It's mostly a discussion of the theories of James Tabor (professor of religious studies, UNC-Charlotte) which he describes in his book, The Jesus Dynasty: The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity. The article also describes the general direction of scholarship regarding Jesus and the origins of Christianity. Tabor's is another of those analyses of the story of Jesus, trying to distinguish what is perceived to be historical versus what is perceived to be fictional.

According to Tabor, Jesus, in partnership with his cousin John the Baptizer, saw himself as the founder not of a new religion but of a worldly royal dynasty. Fulfilling ancient prophecies, the dynasty, descended from King David, was destined to restore Israel and guide it through an apocalyptic upheaval culminating in the Kingdom of God on Earth. And all of this was to happen not in the distant or metaphorical future but in the very time in which they lived. Although their message was one of peaceful change, Jesus knew that he and John had aroused the suspicions of the native Herodian rulers of Palestine as well as their Roman overlords. To carry out his work, Tabor says, Jesus had established a provisional government with 12 tribal officials and named his brother James--not Peter, as traditional Christianity holds--as his successor. And indeed, according to Tabor, James later became the leader of the early Christian movement. What Tabor attempts is not completely new. As far back as the 18th century, Enlightenment scholars sought to separate the facts about Jesus and his early movement from the theological interpretations that supposedly distorted them. That quest, pursued by a variety of seekers with diverse motives and methods, has produced strikingly different accounts of Jesus, his mission, and the Christian movement. But often Tabor must look beyond the Scriptures to support his claims. Why, for example, does he think that Jesus did not institute the "eat my body/ drink my blood" tradition at the Last Supper? Again, he calls this liturgical tradition an invention of Paul, recorded in Corinthians and picked up by Mark. Matthew and Luke follow Mark, but John does not. Tabor admits that he needs an independent source to challenge the idea that Jesus would have broken with the Jewish tradition of blessing the wine and then the bread--and, even more significantly, that he would have violated a strong Jewish taboo against even symbolic cannibalism. Tabor admits that his book uses evidence creatively. "It takes on a novel quality that is imaginative, I hope in a way that is consistent with the facts," he says. Other scholars working on early Christianity agree. "It sounds like a creative reimagining of the historical material, more like historical fiction than history," says Boston University scholar Paula Fredriksen. But her concern is that the imaginative reconstruction may lead to pat conclusions that are not faithful to the complexity of the facts. Tabor makes much of the Epistle of James as representing the view of Jesus's brother, but Fredriksen cautions that "Most people would not accept that 'James' was James." Fredriksen registers a more general caveat about Tabor's book: "It illustrates how plastic the evidence is," she says. Despite the big midcentury finds and ongoing discoveries, the evidence is still so sketchy that it can be taken to support conflicting or opposing arguments. Indeed, a number of other recent books draw on the modern research into the Jewishness of Jesus but come to conclusions quite different from Tabor's.

Theme by Danetsoft and Danang Probo Sayekti inspired by Maksimer